The American Dissident: Literature, Democracy & Dissidence

The Pushcart Prize

I invite other writers to consider the fact that by accepting the prizes and approval of these vague institutions we are admitting their authority, publicly confirming them of the final judges of literary excellence, and I inquire whether any prize is worth that subservience.

—Sinclair Lewis, “Letter to the Pulitzer Prize Committee”

I have never been nominated. But I have had the priviliage [sic] and honor to be in magazines that have won Pushcarts and I have seen my writing alongside some of the winners. I would very much like to get a nomination someday and I would very much like to win the prize. And there aren't many other prizes I covet. I bring this all to your attention, because Katrina, my girlfriend, my wonderful other, has just yesterday received her second nomination, this time from the Melic Review. The wonderful and talented Katrina has shrugged off this accomplishment, perhaps not wanting to rub it in my face that she has been nominated twice and I have heretofore not been nominated at all. But there is no danger of me feeling jealous. I am elated for her, and also for myself. I always wanted to date a celebrated poet. Maybe someday someone will nominate me. I have no idea. It's not the kind of thing you can shoot for. If it happens, it happens. Katrina Grace Craig, multiple Pushcart nominee. It has a nice ring, doesn't it? Job well done, Katja. Job well done.

I have never been nominated. But I have had the priviliage [sic] and honor to be in magazines that have won Pushcarts and I have seen my writing alongside some of the winners. I would very much like to get a nomination someday and I would very much like to win the prize. And there aren't many other prizes I covet. I bring this all to your attention, because Katrina, my girlfriend, my wonderful other, has just yesterday received her second nomination, this time from the Melic Review. The wonderful and talented Katrina has shrugged off this accomplishment, perhaps not wanting to rub it in my face that she has been nominated twice and I have heretofore not been nominated at all. But there is no danger of me feeling jealous. I am elated for her, and also for myself. I always wanted to date a celebrated poet. Maybe someday someone will nominate me. I have no idea. It's not the kind of thing you can shoot for. If it happens, it happens. Katrina Grace Craig, multiple Pushcart nominee. It has a nice ring, doesn't it? Job well done, Katja. Job well done.

—Jim Valvis, self-proclaimed boyfriend of a multiple Pushcart nominee

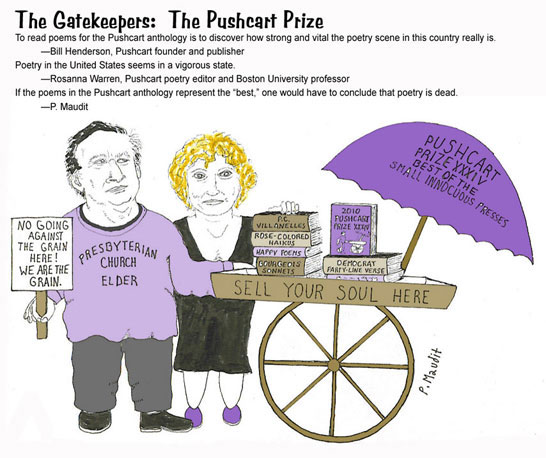

The Pushcart Prize is easily summed up by the simple juxtaposition of the above two quotes and literary cartoon. Compare it with the hagiographic essay appearing in Poets & Writers, Inc.. Unlike that essay, let's raise a few questions. First, who are the judges sitting on the prize panels as literary censors of good taste and artistic excellence, those highly subjective qualities? Second, how are they chosen? In other words, who were the judges who chose those judges? Third, who or what kind of work tends to be chosen for the prizes and, conversely, not chosen? Fourth, how does the prize fit into the schema of the academic/literary established-order milieu?

The answers to those key questions—because they’ll inevitably reveal the degree of intrinsic subjectivity and bourgeois-bias—are not readily announced by literary prize-awarding organizations.

Any independent thinker, as opposed to an MFA-indoctrinated poet, will immediately comprehend that being nominated for the Pushcart Prize is absolutely meaningless. How easy for me to nominate a friend and vice versa. Is that done? Of course! Widespread? No doubt! Has the Pushcart become a vast pool of meaningless nominations of friends by friends, a vicious circle of pushers and self-advocators lacking all respect for objectivity? It is amazing to note how many vaunt being nominated for that Prize. A glance at Yahoo, Google, or Altavista would lead one to surmise that the bulk of recipients being advocated or self-advocating are in fact English professors. Never is there any questioning or challenging by those professors of that Prize.

The Pushcart boasts being the “Best of the Small Presses.” Of course, such a designation must be subjective, despite appearances to the contrary. How many small presses never submit nominations? Perhaps many? If so, how can the Pushcart represent the “Best”? Is that question ever posed? Certainly not by academics and other Pushcart proponents. Interestingly, one must wonder if the poetry in the annual resultant Pushcart Prize anthology is better than that in The Best American Poetry, another annual anthology (see BAP for an unusually critical review).

So, what is the Pushcart? Small-press editors nominate works from their journals in the Fall, which are then reviewed by judges through the Spring. The winners get to have their work appear in a “Best of” anthology distributed by W.W. Norton & Company. Would the judges choose an essay or poetry critical of Norton, the publishing industry, and its literary prizes? What else would they likely not select?

Past winners of the Pushcart read like a who’s who of the Academic/Industrial Literary Complex, including English professors, ex or otherwise, Charles Simic, Robert Pinsky, Joyce Carol Oates, Ray Carver, André Dubus, Margaret Atwood, and Richard Ford. Updike is also a winner, but for some reason never became a professor.

“Fascinating,” writes Time, "an exceptionally strong sampling,” adds New Republic, “invaluable,” declares LA Reader, “a generous and stimulatingly eclectic selection,” states Publishers Weekly, “of all the anthologies, Pushcart's is the most rewarding,” underscores Chicago Tribune. Considering the number of highly boring literary anthologies being published by Norton and others (there’s a hell of a lot of money in college textbooks!), it is difficult to pay heed to the blurbs. Besides, a thinking poet/writer must always wonder what kind of connection exists between the blurbers and the object blurbed.

Booklist seems to sum up the Pushcart best as “new writers follow in the footsteps of established voices.” Indeed, what does that mean? Doesn’t it mean anyone NOT following in the footsteps of the established is likely not going to get the Prize? Well, the judges will no doubt, to avoid being labeled un-objective and academic, make sure to award the prize to a token nonconformist poet and writer. Kirkus Review (Amazon.com) presents a good idea of the type of subjects selected, including the theological-activist career of a father, cases of obsessive collectors, testimony of a grandfather's bookcase, a survey of love in San Francisco, Wild West phantasmagoria, and a drug-addict teacher and her pusher students. Evidently, no critical essays vis-à-vis the academic/literary established-order milieu were chosen. Perhaps the New York Times Book Review blurb for the Pushcart does tell it like it is: "The single best measure of the state of affairs in American literature today." Sadly, that state of affairs has evidently become pervasive socio-politically disengaged, risk-free writing that must surely have Orwell, Ibsen, Emerson, Baudelaire, Jeffers and others turning in their graves.